home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase |

|

|

EDGAR DEGAS (1834-1917)

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/visual_arts/article6935554.ece

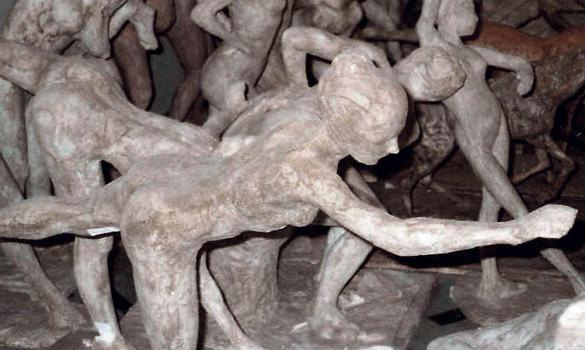

They are either one of the most extraordinary art finds of the past 100 years or one of the most exquisite frauds to be attempted. One way or another, though, a complete set of 74 plaster sculptures of dancers, bathers and horses attributed to Edgar Degas will dominate discussion of the great Impressionist artist for years to come. Bronzes cast from the plasters went on public display for the first time yesterday at the Herakleidon Museum, a private museum in Athens. The organisers of the exhibition are in talks with a number of London galleries about bringing them to Britain next year. Scholars are split over whether the plasters are genuine. If they are, they would represent the purest record of Degas’s sculptural powers in existence. Excitement centres on the claim that these plasters were made during Degas’s lifetime. They correspond to the 74 Degas wax sculptures found intact in his apartments after his death in 1917 and cast and recast since then. Every known Degas statue is taken from these posthumous bronze casts, which carry some trace of deterioration and pick up less of the original detail than a plaster cast would have done. Although he is best known for his pastels of ballet dancers, Degas turned increasingly to sculpting in wax as his eyesight failed towards the end of his life.“I must learn a blind man’s trade,” he said at the time. He worked rapidly, primarily with a soft modelling clay, which he often mixed with beeswax and stiffened with everyday objects such as broken paintbrush handles, sponges and pieces of cork and wire. He never meant these wax studies to be seen and wrote to a friend: “I never seem to achieve anything with my blasted sculpture.” His friend Renoir disagreed, saying: “Why, Degas is the greatest living sculptor.” Degas exhibited only one statue during his lifetime. La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans (The Little Dancer, Age Fourteen) was shown in 1881 at the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in Paris to a mixed reaction. Joris-Karl Huysmans, in L’Art Moderne saluted “the only truly modern attempt I know of in sculpture”. Elie de Mont, in La Civilisation, summed up the opposing view: “This opera rat has something about her of the monkey, the shrimp, the runt. Any smaller and one would be tempted to enclose her in a jar of alcohol.” Today there are an estimated 1,380 bronzes attributed to Degas with examples of The Little Dancer in the collections of the Tate and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The best Degas bronzes still command huge prices. In February a bronze of The Little Dancer sold at Sotheby’s in London for just over £13 million. Bronzes cast from the newly discovered plasters could exceed that if they are accepted by Degas experts. The story of their discovery begins in 2001 when Walter Maibaum, a leading authority on 19th and 20th century European art, heard that a new set of bronzes of The Little Dancer were being cast in France. This seemed impossible as the only two known plasters were in American museums and neither would lend their plaster out for that purpose. Mr Maibaum flew to France where he was led to “an unknown plaster version of The Little Dancer” that differed slightly, from the familiar versions but beguiled Mr Maibaum with its poise and beauty. Its owner was Leonardo Benatov, the proprietor of the Valsuani Foundry, which cast bronze masterpieces by the likes of Rodin and Picasso. Mr Maibaum searched for an explanation of the unknown plaster cast. In the exhibition catalogue he recalls how in 2004, during another interview with Mr Benatov he was “led to a locked room at the far end of the foundry. Inside were 74 other Degas plasters [one was a duplicate] which were completely unknown to anyone outside the foundry or its close associates. It was a shocking sight. To me it was the equivalent of opening King Tut’s tomb in Egypt or uncovering the terracotta warriors in China.” Gregory Hedberg, an art historian attached to a New York art gallery, gathered evidence that includes carbon dating and a series of letters and which suggests that the casts were made during the late 19th or early 20th century for the private use of Degas’s friend, the sculptor Albert Bartholomé. They ended up forgotten and abandoned, eventually passing to the Valsuani Foundry in 1955. Fewer than half a dozen world experts probably need to be convinced for the statues to become a commercial success but at present many of them are put off by what they see as an “aggressive” marketing campaign and insufficient evidence. One leading world expert on Degas said yesterday: “It is not implausible. But there isn’t a paper trail and the way they are hawking it round it really does seem like someone trying to make a big profit.” Steven Nash, director of Palm Springs Art Museum and a specialist in modern sculpture, has examined the plasters and is convinced. “If one accepts Hedberg’s conclusions, this is an astonishingly important discovery ... There is no logical explanation for them other than the one Hedberg is putting forward. There is no other way to explain them.” Mr Maibaum, who owns one set of 74 of the “new” bronzes, said: “Do we have a smoking gun? No, but all the evidence points to the fact that this was what occurred.” Eliot Goldfinger wrote: As author of Human Anatomy for Artists, Oxford University Press, and a realist figure sculptor, I was asked to compare the lifetime plaster of The Little Dancer found at the Valsuani Foundry with the Hebrard bronze of the same subject. I observed that the very accurate anatomy on the lifetime plaster records an original wax figure that was made most likely using a live model. On the other hand, the Hebrard bronze of The Little Dancer shows a wholly different sculpture, modeled with a different intent and focus. It is more about flow of form and impression. In his later modeling, Degas migrated away from his original accurate depiction of anatomical forms, intentionally sacrificing anatomical accuracy, to a more fluid approach to the relationships of the forms. I do not think a model was present for the modeling of the later version. We have here two very different sculptures. They represent an early phase and a later phase of the working process and figurative approach of one artist. They just happen to sit on the same armature. If the early version was not recorded in plaster, we would have never known what Degas originally sculpted in 1881. This discovery is nothing short of a miracle.January 8, 2010 5:42 PM GMT on community.timesonline.co.uk Eliot Goldfinger wrote:

As author of Human Anatomy for Artists, Oxford University Press, and

a realist figure sculptor, I was asked to compare the lifetime

plaster of The Little Dancer found at the Valsuani Foundry with the

Hebrard bronze of the same subject. I observed that the very

accurate anatomy on the lifetime plaster records an original wax

figure that was made most likely using a live model. On the other

hand, the Hebrard bronze of The Little Dancer shows a wholly

different sculpture, modeled with a different intent and focus. It

is more about flow of form and impression. In his later modeling,

Degas migrated away from his original accurate depiction of

anatomical forms, intentionally sacrificing anatomical accuracy, to

a more fluid approach to the relationships of the forms. I do not

think a model was present for the modeling of the later version. We

have here two very different sculptures. They represent an early

phase and a later phase of the working process and figurative

approach of one artist. They just happen to sit on the same

armature. If the early version was not recorded in plaster, we would

have never known what Degas originally sculpted in 1881. This

discovery is nothing short of a miracle. John Spike wrote: I have had more than one opportunity to examine the plaster of the Little Dancer and its fine quality is obvious at first sight -- and then grows from there. Plasters were essential to the 19th century sculptor's working process. Rodin adored them, often exhibited them. For sculptors, plasters were more permanent forms of their clay models. They made them as preparatory for casting in bronze but also as back-ups to clay models in process. Indeed, these plasters sketches and works-in-progress. They're clearly not based on the final bronzes. This is an extraordinary rediscovery!December 30, 2009 10:37 PM GMT on community.timesonline.co.uk Gregory Hedberg wrote: Re: a paper trailEvidence that Albert Bartholomé made plasters from Degas’ waxes is found in a letter from the 1890s. Referring to a portrait bust he was working on, Degas wrote to his friend Bartholomé: "The moment I return I intend to pounce upon Mme. Caron. You should already reserve a place for her among your precious bits of plaster." (See Degas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988, p. 455). There is also documentation that plasters owned by Bartholomé remained with his second wife until 1955, the year other evidence indicates that the Degas plasters were taken to the Valsuani Foundry in by Palazzolo. Archival research undertaken by Louise d’Argencourt revealed that Bartholomé’s art collection, apartment and studio remained largely intact until 1955. Although Bartholomé died in 1928, his art collection remained with his second wife Florence Letessier (died 1959). D’Argencourt discovered that Letessier lived in the same rue Raffet apartment with Bartholomé’s adjacent studio from 1901 until she was forced out and into an asylum in November 1955. One listing in the November 1955 inventory taken when Letessier left recorded: “Dans l’atelier, un lot important d’études en plâtre…” While this listing refers to Bartholomé plasters, it documents that plasters were preserved in his studio until 1955. Then, in June of 1956, there were two auctions at the Hotel Drouot of various works of fine and decorative art from the Estate of Albert Bartholomé. All this evidence suggests that lifetime Degas plasters were made by Bartholme in the 1890s. They then could easily have remained with the rest of Bartholomé’s art collection until 1955; the year the plasters were taken to the Valsuani Foundry. There is also a paper trail indicating that by November 1955, new Hébrard casting activity was already taking place. There is no paper trail of the only alternative, namely, that some 70 wax copies of Degas waxes were ever made and from these copies plas December 14, 2009 7:03 PM GMT on community.timesonline.co.uk Audrey Flack wrote:

Putting aside any feelings I have about the ethics of profit seeking

from posthumous bronze castings, I offer my opinion as an artist,

painter, sculptor and professor of anatomy. The "Little Dancer" by

Degas that Gregory Hedberg showed me the other day is a superior

piece whose gesture and anatomical components ring true. It holds

within it the hand and intent of an artist, Degas, who knew his

anatomy and could capture the pose of the model. Graydon Parrish wrote:

For the record, Dr. Gregory Hedberg was the discoverer of the Degas

plasters discussed in the Times. Why? He was the first to recognize

and then provide extensive evidence that The Little Dancer plaster,

plus the menagerie of smaller plasters found at Valsuani, were cast

from the original waxes while Degas was still alive. Everyone else

thought they were foundry models made by Palazzolo after Degas'

death. Guy Sainty wrote:

Regarding the suggestion that the foundry could have used "old

materials" - one cannot reuse plaster once it has been cast in a

mold, so there is not the slightest possibility that Valsuani used

"old materials" (i.e. plaster) to recreate plasters. Furthermore how

would they have done so in the dozen or so cases where the casts are

clearly made from Degas waxes as they were before they were broken

and repaired, or even altered by the artist - Degas reworked some of

the waxes and made some changes. Some of the repairs, reflected in

the bronzes cast from the posthumous plasters, are quite

unsatisfactory, whereas the Valsuani plasters show models before

they were damaged. Guy Sainty wrote:

I have studied some of these original Degas plasters in New York,

including the plaster of The Little Dancer, and have also seen

several of the bronzes cast from them. I have no doubt that these

are indeed what they are presented as being – the bronzes are

clearly of higher quality than the Hebrard bronzes that are cast

from the posthumous series of bronzes made from the waxes that

remained in Degas’ studio until his death. Since all Degas bronzes

are posthumous, it really does not make much ethical difference

whether they were cast 1935-55 (when most of the Hebrard bronzes

were made) or in the last decade. The record of the Hebrard

posthumous casts is actually confirmed in a recent publication of

the Norton Simon museum Degas in the Norton Simon Museum. This

includes important new scientific evidence of the links between

Palazzolo, the master founder for Hébrard, and the Valsuani Foundry

in Paris where the Degas plasters were found. Chemical analysis of

the modèle Degas bronzes undertaken by conservators Daphne Barbour

and Shelley Sturman found that four of the modèle bronzes had

patinas that contained chromium. They note that chromium was not

used by Hébrard, but was typical of the Valsuani foundry and is

found in Valsuani Matisse bronzes. They also suggest that the Norton

Simon bronze of The Little Dancer may have been made later at the

Valsuani Foundry and that this example is actually cast from a

bronze (a surmoulage) Elizabeth Lebon in her recent publication (Dictionnaire

de fondeurs de bronze d’art: France, 1890-1950, 2003) also records

definite ties between the Valsuani and Hébrard foundries. These new

scientific studies help to explain why these Degas plasters ended up

at the Valsuani Foundry in Paris. The Degas Little Dancer’s known

today have important differences from the bronze cast from the newly

discovered plaster, which actually conforms much more closely to the

description of the original exhibited by Degas at the Salon. Gregory Hedberg wrote: Shon Reid is correct. The Degas plasters were not just "discovered." When Benatov bought Valsuani in 1980, they were in a warehouse along with plasters by Rodin, Bugatti, and Pompon.Benatov thought the Degas plasters were simply posthumous foundry plasters made by Palazzolo. Because the droit moral for Degas would not expire until the 1990s, the plasters could not be cast and were therefore just locked away. My scholarly interest is in the plasters, but I think the new Valsuani bronzes are magnificent. They are not surmoulages like almost all of the Hébrard bronzes. They were cast from lifetime plasters and therefore all of the current Degas heirs have officially approved this new edition by Valsuani. Carbon Dating: By 1980, the Valsuani foundry had closed and Benatov now brought the equipment to his new foundry in Chevreuse, outside of Paris. Therefore, the suggestion that there was old foundry material lying around makes no sense. Carbon Dating tests showed that the abaca fibers imbedded into the plasters date from before the Atomic Age, before 1950-55, nothing more. Significantly, some 300 measurement comparisons show the plasters to be routinely 1 to 3% larger than the modèle Degas bronzes. Recent test cleanings also revealed some very old repairs to the plasters. Some of the plasters record bases and other elements found in the 1918 photographs taken of Degas' waxes, but not found on the Hébrard bronzes or the waxes today. While there are many similarities, there are also some important differences between the plasters and the Hébrard bronzes, i.e. they are not posthumous foundry plasters. The most important insight these lifetime plasters reveal is that the Degas waxes today are generally very close to the way they looked in the 1890s when most of these plasters were made. As a result, numerous scholars, museum curators and conservators are very excited about these plasters, and the bronzes, not just art dealers. Dr. Gregory Hedberg December 1, 2009 9:29 PM GMT on community.timesonline.co.uk graydon parrish wrote:

The issue of price, profit and marketing, aggressive or subtle, are

red herrings in this debate. The statues either are by Degas or they

are not. Whether posthumous casts are legitimate works of art is

another subject altogether. What this discovery will reveal is the

politics of the art world and the limits of expertise. That is, what

makes an expert and how can science assist in authenticating works

of art. Leslie Kessler wrote:

Even if the figures were made by Degas during his lifetime,

posthumous casts present an ethical problem in terms of value and

the meaning of the word "authentic." I would caution anyone

considering the purchase of such a cast to think twice. Ambrose Ambrose wrote:

From the photograph, it doesn't look as though they're looking after

these fragile objects particularly well. I've got a vision of 74

objects being crammed into a tea chest. Robert Persey wrote:

I would be interested in these sculptures if they were significantly

different in form to the known Degas works because we could then

evaluate them as sculpture and that would be exacting and exciting.

If they are copies taken during his lifetime it would be instructive

to compare them with the waxes found after his death which would

have almost certainly been reworked and more recent versions. Dirk Bruere wrote: The only people who care whether it's by Degas are those who are more interested in price than art.November 28, 2009 7:43 AM GMT on community.timesonline.co.uk |

|

|

|

E-mail: info@hayhillgallery.com |