home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase |

||||||

|

ROBERT BISSELL

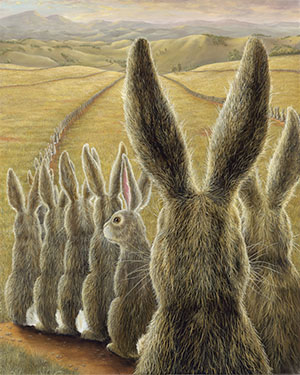

‘Whatever happens to the beast also happens to the man. All things are connected’ Chief Seattle, Suwamish Tribe Robert Bissell’s paintings could have been lifted from the pages of a children’s well-loved story book, but closer inspection reveals a far deeper meaning. Like animals from Aesop’s fables or Watership Down, the timeless philosophy of each subject leads us into powerful childhood memories- and the innocence of who we really are. His creatures challenge our forgotten sense of play with disarmingly Narnian wisdom; we find that the fairytale symbolism still resonates with an adult spirit.

In ancient mythology, animals carried their own symbolism, existing as omens for interpretation. A fox slinking in the shadows is a glimpse into the supernatural; a horse galloping across the field is a promise of strength and freedom. In the attempt to make sense of human existence, we are looking for moral authority- and find it in living breathing furry metaphors. Unable to fully detach, we will see certain human traits in animals long before we recognise them in ourselves. At one with their environments- and at peace with themselves- the animals reveal things hidden from human eyes. They continue to teach us about the possibility of less cluttered lives, allowing earth to connect with an uninhibited spirit

Why animals? When I showed the picture to friends, everyone gravitated toward the mouse. I realised that having animals in the painting was a way to draw people in and enable them to connect with the natural world. So they got bigger, and bigger still, until eventually they became the setting for the story. It made it easier to show the beauty I saw in the landscape, but it also enabled me to show the beauty I saw in humans. People talk about anthropomorphism in my work, but I prefer to think of humans as having animal characteristics rather than the other way round. I don’t really apply human qualities to any of my paintings. I don’t even sign them: I don’t want a human element in there, it would distract from the natural world.

Why bears and rabbits in particular?

What do you think drew you toward nature in the first

place? To me, children’s literature and my experiences on the farm weren’t that different. This was formative, though would not come into play until much later. I got distracted—and attracted—by city life as a means of escaping the somewhat conservative and repressive environment of my home and boarding school. Art school, the big city and moving to the USA to work in design and advertising were a means of breaking away.

Why do you think people lose touch with nature?

How have people responded to your work?

How do you go about creating a new painting? I try not to get too anthropomorphic about it. The idea is to get people thinking, are these animal poses or human ones? The painting of the bear diving, for example—that looks human, but it was actually modelled on a photograph of a real bear diving.

Tell us about the

Hay Hill

exhibition.

Animals are good for

thinking Robert Bissell is a painter of naturalism and fantasy, combined and influenced by Romanticism. While his works touch upon wonderment, they offer a convincing view into a world without ‘civilization,’ wherein the viewer is mesmerized by the power of light and the essence of natural law – yet tinged by fancy. This genre of art is sometimes called Magical Realism. Early tribal cultures believed the natural world to be the bridge connecting earth and spirit. Animals were regarded as powerful spiritual beings that could connect humans to unseen realms, the environment, and each other. Along these lines, Robert Bissell creates works that transport us into a completely different atmosphere than that of modern daily life, inviting us to learn more about ourselves and to contemplate our origins in the natural world.

Bissell's paintings explore the idea that animals have metaphysical importance to our own spiritual well-being. Lured into a realm absent of humans, Bissell’s animal characters ask that we consider our own condition and place in nature. While whimsical at first glance, there is underlying tension and precariousness beneath the images. Disarmed, we objectively consider ourselves without familiar references. "His animal work is full of charged meaning and lore, and it’s touched by surrealism", says Suzanne Bellah, Director of the Carnegie Art Museum. “Influenced by the surreal legacy of Magritte, he mixes scales and uses gigantism with a variety of textures and subtle color palettes.” Indeed, Bissell keys his palette to the great landscape masters of European art Claude Lorrain and Corot (France) and Thomas Gainsborough (England). Imaginary Realist Robert Bissell creates a completely different atmosphere from our daily experience, inviting us to learn more about ourselves. In his paintings the world of animals is a mirror for human existence, self-definition and reflection. These are not mere children's tales - quite the contrary. Bissell's work causes us to reflect on the environment, life, death, renewal and the stages of transition - departing from the safety of family, and making our way in the world. Bissell grew up on a farm in Somerset, England, where animals, Celtic legends and panoramic landscapes were part of his daily life. His keen interest in visuals began at an early age, documenting life around him through photographs. He would spend hours stalking wildlife on the moors close to his house to see how close he could get before they would sense his presence. But ultimately, country life was not for him and Bissell headed for the city to study art. After earning his bachelor’s degree at the Manchester College of Arts and Technology, Bissell moved to London for post-graduate work in fine art photography at the Royal College of Art. After completing his studies, Bissell spent four years traveling the world, working on cruise ships to pay his way. In 1982, after settling in San Francisco, one of his favorite ports of call he began working for The Sharper Image as photographer of its high tech merchandise. For the next decade he moved up the corporate ladder, during what is arguably the companies most exciting time, to become head of the creative and merchandising divisions. In 1992, he left the company to start his own retail catalog company in Portland, Oregon, which was eventually sold to Readers Digest. In 1995 he began to wonder if the long-term implications of the industry he was engaged in really fit his world-view. The catalogs he was producing wasted a great deal of paper with very little return. Trees destroyed for paper, most of which was just thrown away. The corporate world had also taken its toll. Bissell missed art. He decided it was time to explore the possibilities of telling people about nature and his view of it though painting. He had studied drawing in college and believed that it was simply a matter of wanting it – and teaching himself to paint. “I had forgotten why I wanted to be an artist in the first place,” he said. “I wanted to get that back, and I am glad I did before it was too late.” Pagans and Celtic Christians believed the natural world was the bridge that connected earth and spirit, with animals acting as spiritual intermediaries. Now, most people live in cities and suburbs, separated from that world. “Animals used to be involved with humans as messengers with magical functions,” he says. “Now they are our slaves for consumption and entertainment. I wanted to restore their role and give them a new voice.” Since then he has devoted all this time to painting. He regularly exhibits in museums and galleries across the United States and Europe. Bissell hopes his paintings appeal to the intellectual child in us, reminding us of the mythic and universal human values in the tradition of the great heroic-quest stories. His work encourages us to reflect on nature, the roads we travel, and the choices we make along the way. His story encourages us follow our passions and have the courage to do what is meaningful to us – whatever that might be.

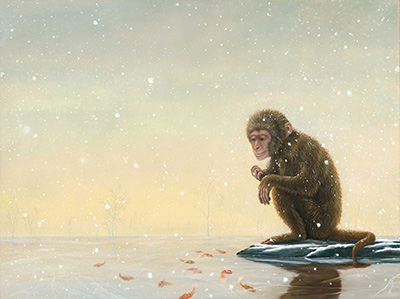

The environment and humans relationship to it has always been a fundamental aspect of my work and in recent years I have found myself reacting even more to the vast changes our natural world is experiencing. Looking back over the work displayed here I am aware that a narrative was being created as I painted. Beginning with Inspiration (the first painting I did in this series), the figure looks up with wonder at the waterfall, a source of creativity and imagination. In Supernova, our protagonist pays homage to the universal forces that sustain us. In The Race our elephants rejoice and play in the elements that support them and In Mono No Aware, the figure contemplates a gentle falling snow by a frozen lake as it's inhabitants swim below. How more perfect can this world be that surpasses anything humans can create? In The Mountain, our figure faces a seemingly great challenge with an overwhelming oncoming tide and in Meeting on The Ice we are presented with an enigmatic scene as we imagine polar bears travelling south in search of new habitats. Finally, the fragility of animal and human existence is presented boldly in Titan as this majestic black rhino challenges us to contemplate our own influence over the natural world.

Robert Bissell

Selected Recent Exhibitions

2019 Lahaina Gallery, Newport Beach PUBLISHED WORK/AWARDS:

Spirit, The art of

Robert Bissell,

Spring 2019

EDUCATION:

https://www.borsini-burr.com/artists/robert-bissell

You have said you don't like to talk in detail about

your paintings. Why is this?

The animals in your paintings seem to be speaking to

us about human concerns and values. Why not paint humans in human

situations?

What is so fascinating to you about these animals in

particular? Why so many rabbits and bears?

The large animal portraits, the Eden paintings, are

so formal and direct. The viewer is face to face with an animal that

seems to be their equal in size. What are they about?

What is the significance of these particular animals

and where do the landscape settings come from?

Your work seems to have environmental concerns. Is

this a priority for you?

There seem to be spiritual references in your work.

What are the implications here? Are you a religious person?

Wait a minute - you're starting to sound like a

missionary. Do you consider your work a way of talking to people,

saying there is a better way?

If artists don't start talking about contemporary problems and worldly issues, providing a moral stance, high art is going to be swallowed up by a rabid pop and corporate culture. And, at the risk of sounding elitist, I'm prepared to take a stand in this effort. If the world is going to be saved, it's not going to be by politicians, corporations or religious fundamentalists - artists can help us understand the relationships between nature and humankind.

What is your involvement with animals outside of

painting them?

Why did you decide to paint?

Which artists do you admire or respond to?

What makes your art successful for you?

In his amazing paintings, Bissell creates and transports us to a completely different atmosphere from modern day life and invites us to learn more about ourselves. In his work, the world of animals is a mirror for human existence, self-definition and self-reflection. Yet these are not mere children’s tales. His animals have a metaphysical importance to our own spiritual well being. Lured into a realm, devoid of humans, the animal characters make us consider our own condition and place in nature. “Bissell’s work disarms by narrating vitally grown-up and urgent allegories in the guise of child-like humor,” William Zimmer, art critic from The New York Times warns. Conjuring up something simultaneously real and unreal, these images appeal to the intellectual child in all of us. Bissell’s work is a reflection on the environment, life, death, renewal and stages of transition. His landscapes offer no familiar frame or reference. The viewer can wander freely into the scene and consider it according to their own sensibility. These are not romantic landscapes in the traditional sense. Rather, they allow an experience of the sublime, not from what may be, but from what it is. Robert Bissell believes his work is successful when it takes someone’s breath away, even for a second. It brings them out of themselves to a place of different awareness, somewhere quiet and beautiful.

Bissell grew up on a farm in Somerset, England, where animals, Celtic legends and panoramic landscapes were part of his daily life. His keen interest in visuals began at an early age, documenting life around him through photographs. He would spend hours stalking wildlife on the moors close to his house to see how close he could get before they would sense his presence. But ultimately, country life was not for him and Bissell headed for the city to study art. After earning his bachelor’s degree at the Manchester College of Arts and Technology, Bissell moved to London for post-graduate work in fine art photography at the Royal College of Art. After completing his studies, Bissell spent four years traveling the world, working on cruise ships to pay his way. In 1982, after settling in San Francisco, one of his favorite ports of call he began working for The Sharper Image as photographer of its high tech merchandise. For the next decade he moved up the corporate ladder, during what is arguably the companies most exciting time, to become head of the creative and merchandising divisions. In 1992, he left the company to start his own retail catalog company in Portland, Oregon, which was eventually sold to Readers Digest. In 1995 he began to wonder if the long-term implications of the industry he was engaged in really fit his world-view. The catalogs he was producing wasted a great deal of paper with very little return. Trees destroyed for paper, most of which was just thrown away. The corporate world had also taken its toll. Bissell missed art. He decided it was time to explore the possibilities of telling people about nature and his view of it though painting. He had studied drawing in college and believed that it was simply a matter of wanting it – and teaching himself to paint. “I had forgotten why I wanted to be an artist in the first place,” he said. “I wanted to get that back, and I am glad I did before it was too late.” Pagans and Celtic Christians believed the natural world was the bridge that connected earth and spirit, with animals acting as spiritual intermediaries. Now, most people live in cities and suburbs, separated from that world. “Animals used to be involved with humans as messengers with magical functions,” he says. “Now they are our slaves for consumption and entertainment. I wanted to restore their role and give them a new voice.” Since then he has devoted all this time to painting. He regularly exhibits in museums and galleries across the United States and Europe. Bissell hopes his paintings appeal to the intellectual child in us, reminding us of the mythic and universal human values in the tradition of the great heroic-quest stories. His work encourages us to reflect on nature, the roads we travel, and the choices we make along the way. His story encourages us follow our passions and have the courage to do what is meaningful to us – whatever that might be.

Taking a cue from the Romantic period, Bissell invokes a sense of peace and harmony in his paintings with the use of soft light and contemplative animal figures in idyllic landscapes. In The Embrace, bears stand upright, looking skyward, surrounded by swirling blue butterflies. Yet Bissell doesn’t anthropomorphize animals. Rather, he zoomorphizes people, telling the story of the human condition through animals. His creatures often look us in the eye and invite us to step into their world to see ourselves, once again, as part of nature. “Guardians and guides of the natural world,” Bissell says, “animals challenge us to consider our place and role in a higher order.” “Animals used to be involved with humans as messengers with magical functions,” he says. “I wanted to restore their role and give them a new voice.” And while the child in us may be delighted with the bears and bunnies, a sense of danger, perhaps a storm brewing, pervades many of Bissell’s works. His creatures have a depth of character not found in most children’s illustration. Hero: The Paintings of Robert Bissell (Pomegranate, 2013) follows mythologist Joseph Campbell’s archetypal hero’s journey. In Orion (January-February 2014), Scott Gast makes note of Bissell’s recurring use of bears, rabbits, frogs, and elephants looking skyward “in contemplation of some great mystery beyond the page. It’s the articulation of that mystery that seems to be Bissell’s primary concern as an artist.” “I try to transmit a feeling of oneness and unity in a painting,” Bissell says. “To me it is critical my work promotes an integral understanding of our world, helps raise consciousness, and transforms people’s lives.” After studying photography at the Manchester College of Art and completing a postgraduate course in fine art photography at the Royal College of Art in London, Bissell left England to work as a photographer on a cruise ship, eventually settling in San Francisco where he built a successful career in advertising. He then started his own catalog company in Portland, Oregon, but gave it up and taught himself to paint. Bissell keeps in touch on Facebook. More about the artist can be found on his website. |

||||||

|

|

E-mail: info@hayhillgallery.com |

|||||

Talk

to the Animals

Talk

to the Animals Bissell

is the master of altering perspectives: one minute we are peering

down on a softly whimsical scene of bears and butterflies; the next

we are dwarfed by a giant rodent (with every single one of his ratty

hairs glistening in high definition). Some characters are too big

for their worlds; others nearly lost in the sprawling landscape.

Bissell’s animals in some way hold up a mirror to our own triumphs

and failings- unmasking our callings, journeys and secret desires.

Although the artist’s technique is remarkably realistic, his

creatures appear surreal- as though clones of each other. There is

not a group of wolves, only one universal wolf repeated across the

canvas. In this way, the works have the golden enchantment of a

dream, provoking an out-of-body experience for the viewer.

Bissell

is the master of altering perspectives: one minute we are peering

down on a softly whimsical scene of bears and butterflies; the next

we are dwarfed by a giant rodent (with every single one of his ratty

hairs glistening in high definition). Some characters are too big

for their worlds; others nearly lost in the sprawling landscape.

Bissell’s animals in some way hold up a mirror to our own triumphs

and failings- unmasking our callings, journeys and secret desires.

Although the artist’s technique is remarkably realistic, his

creatures appear surreal- as though clones of each other. There is

not a group of wolves, only one universal wolf repeated across the

canvas. In this way, the works have the golden enchantment of a

dream, provoking an out-of-body experience for the viewer.

In his animal paintings, the world of animals is a mirror for human

existence, self-definition, and self-reflection. Yet, these aren’t

mere children's tales. "Bissell's work disarms by narrating vitally

grown-up and urgent allegories in the guise of child-like humor,"

counters William Zimmer, art critic for The New York Times.

In his animal paintings, the world of animals is a mirror for human

existence, self-definition, and self-reflection. Yet, these aren’t

mere children's tales. "Bissell's work disarms by narrating vitally

grown-up and urgent allegories in the guise of child-like humor,"

counters William Zimmer, art critic for The New York Times.  This Universe of Life

This Universe of Life

Imaginary

Realist Robert Bissell creates a completely different atmosphere

from our daily experience, inviting us to learn more about

ourselves. In his paintings the world of animals is a mirror for

human existence, self-definition and reflection. These are not mere

children’s tales – quite the contrary. Bissell’s work causes us to

reflect on the environment, life, death, renewal and the stages of

transition – departing from the safety of family, and making our way

in the world.

Imaginary

Realist Robert Bissell creates a completely different atmosphere

from our daily experience, inviting us to learn more about

ourselves. In his paintings the world of animals is a mirror for

human existence, self-definition and reflection. These are not mere

children’s tales – quite the contrary. Bissell’s work causes us to

reflect on the environment, life, death, renewal and the stages of

transition – departing from the safety of family, and making our way

in the world.

As

a child growing up on a farm in the English countryside, Robert

Bissell immersed himself in the world of animals—the sheep, pigs,

and chickens of the family farm, and the owls, rabbits, and wild red

deer of the countryside. Add to his upbringing a liberal dose of

literature, from

As

a child growing up on a farm in the English countryside, Robert

Bissell immersed himself in the world of animals—the sheep, pigs,

and chickens of the family farm, and the owls, rabbits, and wild red

deer of the countryside. Add to his upbringing a liberal dose of

literature, from