home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions press

contact

purchase |

|

|

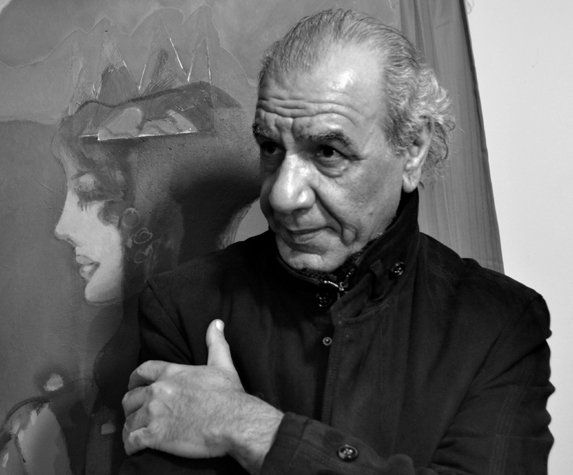

HANI MAZHAR

Artist's Statement I call the colours by their agreed names, Blue, Yellow, Red… Yet when I am facing my painting, these names cease to have a meaning, as each painting has its own concept and language, and I find myself obliged to learn the basics of dialogue with a new language and mind set. I cannot claim that I know what I want from my painting, or what the end results are for I do not find myself in a specific place or time. Sometimes I think that this justifies my obsession with the wings that I place on human shoulders, are they human beings? I do not find a meaning of a place or a time. There is no difference to me between Babylon and Uruk or London and Tokyo. Moreover, I have no desire to belong to a specific era. Perhaps the elements of my painting are mixed and dispersed between various places and eras that are connected together by a mysterious feeling of life… Let’s call it intuition. As Bergson said: Realising matter by considering it a mental state.'

Countless Shades In short, metaphorically speaking, I find in these images unlimited fields to capture my needs of roses and wood. This total mess provides me with the absolute freedom to choose my subject before I detail it on the painting, responding sometimes to a mysterious call or a certain sign that determines where the painting should go. This happens without pre-planning as I deliberately avoid any preparation mock before I begin painting. I follow the sign, willy-nilly, to where ever it takes me. Therefore, lines, shapes and colours are all a collection of coincidences that coincidentally converge on the mind’s countless shades. Hani Mazhar

Not Iraqi or English, just creative without

borders Hani Mazhar sits in Spica Gallery in Tokyo’s Minami-Aoyama, looking unlike any artist ever met. He wears a double-breasted jacket with silver buttons, carefully pressed trousers, immaculately polished shoes. A perfectionist in more ways than one. Some 20 of his paintings hang on the walls. On a table, two “books” in exquisite handmade boxes — limited editions of hand-scribed writings by famed Iraqi sages and associated printed images. As he explains softly, politely, one edition — as loaned by promoter Astrid de los Rios, of Montealto International, who curated this East to East show and specializes in what she calls “nomadic artists” — is based on writings by the 10th century Sufi master al-Hallaj. (The other nine copies are all in museums and private collections.) The second edition (this time for sale) also consists of a set of prints — illustrated interpretations of a selection of poems by the Sufi poet al-Niffari, written out in Arabic, but with an added translation in French. Hani was born in Assamawa, south of Baghdad, an area associated with the Old Testament and the alleged site of Noah’s Ark. He was a mystery to his family, drawing and painting his way to the Institute of Fine Art in the capital. Here he came under the influence of the painter Shakir Hasan al-Said. “Al-Said was a leading member of the Baghdad Group of modern art, founded in 1951,” Hani says. “He envisioned a renaissance — creating a distinctive Iraqi movement that would reforge the links that separated artists from the age of al-Hallaj.” But in the 1970s, corruption set in. “Political leaders began applying pressure to artists to use their talents for propaganda purposes. Asked to devise and promote a new nationality for our country. I began asking myself, what is nationalism?” Since the time of the biblical flood, he says, Iraq has been a sad country, its people a sad people. “Sorrow has passed down through the generations for so long I believe it’s now genetic. Even when we sing, we cry.” On the last day of 1978, forced to submit to political will, he left Baghdad. “I spent two years living with the marsh Arabs. Quiet and beautiful, yes, but like living in the 14th century.” With no materials for painting, he spent most of his time reading. In the capital he had been a star, the top student. In the marshes, his creative wings were clipped. He tried to reach Bahrain by cargo boat. He sought asylum in Morocco. Eventually he found refuge in Kuwait. The day before it was invaded by Iraq in 1991, he left for London. “Overnight I lost 15 years of my life and all my friends. Before they had asked, ‘Tell us why you don’t like Saddam Hussein.’ Suddenly I was lumped with the invaders because of my nationality.” Two weeks after arriving in London he got a call from an Arab newspaper, and has worked for them ever since as a political commentator and cartoonist. Based on art exhibitions in Kuwait (with gold medals in 1983 and 1984 and a special award of appreciation in 1986) he soon had his first one-man show. He shared his last exhibition in 2001 with Japanese artist Akiko Yamaguchi. It was just after Sept. 11, which threatened to paralyze everything. “But we went on, had a panel discussion. The ambassador of Paraguay (de los Rios’ ancestry is Spanish-Paraguan) said it was a good moment for the show, which linked the Middle East with Europe, Asia and Latin America. It showed the world that life was not just about terrorism, but was in effect borderless.” Asked about Yamaguchi’s contribution, Hani explains that when al-Hallaj was crucified in Baghdad for his Sufi faith, a student threw him a rose. “Akiko sculpted roses, attached them to real stems, then shaped the installation to resemble a teardrop climbing into the light.” Themes Hani has explored in the past include the sorrow of Iraqi women and the artist as a nomad, travelling around the world seeking inspiration and answers. This exhibition focuses on the words and poems of al-Hallaj and al-Niffari, with paintings and prints portraying the artist’s intense personal journey through centuries of his country’s history, culture and faith to the present day. Canvases that appear graphically spare are in fact layered with figurative, geometric and abstracted images, and Arabic text, but hidden away. As in Sufism, the meaning is behind the thinking, behind what you see. There is a spiritual quality that gives his work depth and power. Images have their own special rhythm: the more you look, the more you see. “I’m not trying to translate or explain Sufi teachings,” he says. “Rather I’m inviting you to share my own personal vision. One must abandon the usual frame of reality. . . . As al-Hallaj wrote: ‘I have seen my Lord with the eye of my heart and I said, “Who are you?” And he said: “You.” ‘ “ The U.K. has a long tradition of incorporating immigrants into its mainstream. “I have British nationality now, yet was unable to attend my mother’s funeral in Iraq, and I haven’t seen my brother for 25 years. Does this qualify me for a silver medal in exile, I wonder?” Hani — whose name ironically means “happy” and “comfortable” does not really regard himself as an an exile, or as a political refugee. “I’m human. What is nationality anyway? I hate politics. I’m neutral. As in a game of football, I wait to see who loses and support them.” The U.K. seems split down the middle, into those who want Prime Minister Tony Blair to back U.S. President George W. Bush in attacking Iraq to topple the current political regime, and those who are against causing a sad country even more pain. Hani’s own feeling? Iraq needs to solve its own problems. “When tanks roll in, their noise deadens everything. So really, I ask you, what is the meaning of war?”

Crossing the Borders of Space and

Time, our existence today is marked by a tenebrous sense of

survival, living on the borderlines of the ‹present›...The beyond is

neither a new horizon, nor a living behind of the past... We find

ourselves in the moment of transit where space and time cross to

produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and

present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion.

Over the years Hani Mazhar has created cycles of paintings that chronicled mythical events, paid homage to features of his native culture, or were inspired by its rich literary and spiritual heritage. The artist's choice of subject matter, however, does not align him within the Oriental tradition of painters who related their work with Eastern literature, poetry, and calligraphy rather Mazhar plays with this knowledge in order to nonchalantly convey his message of attention to the future, and of his rejection of the present situation. Mazhar's earlier work overflows with mythological references and encompassed symbols borrowed from the ancient civilizations of Sumeria and Assyria. The Gilgamesh series, Fatima's Sorrow, and Pilgrimage originated in Mesopotamian (Iraqi) sources. Thus, although they evoke a certain nostalgia for the past, they equally portray contemporary realities as filtered through the artist's lucid vision. He builds his pictures by mixing vestiges of his Arab heritage with the techniques of modern art. Mazhar's conception of art is not simply the recollection of antiquity for his work engages the viewer with a renewal of the past by presenting us with images which, though they might appear recognizable at first sight, contain deeper levels that pose a number of questions which could relate to Bhabha's notion of the ‹hybrid.› As a creator, Mazhar's quest for freedom of expression deeply influences his visual vocabulary and leads him through a continuous journey of discovery that hovers between abstraction and figuration, mysticism and eroticism. Picasso once said, 'There is no abstract art.' In Mazhar's case, he may start by facing the canvas with a certain image or idea, but by the time the work is completed, a very different figure often emerges. The artist becomes a receptacle for all sort of fertile influences and stimuli. He paints what the intellect dictates, guided by his instincts, in order to unload himself of images and emotions. Upon settling in England in 1990, Mazhar choose the story of the ancient Mesopotamian King Gilgamesh as the subject of his first exhibition in London. He did this in order to suggest that this ancient epic's philosophical references are still valid today. He implies that, in spite of the King's failure to gain immortality through the ingestion of magical herbs, his legacy still remains. Gilgamesh left behind a name that endures by shifting his attention away from his small personal desires toward much loftier pursuits. Ultimately, Mazhar is pointing at the supremacy of art over the erosion of society and the contingencies of history. As Mazhar himself has said, 'the meaning of life lies not in its length, but in its content; it is the target that gives it its full meaning.' Mazhar's Birds of Exile series, created in the late 1990s,was a collection of extraordinary beings, winged creatures, in hues of blue, perambulating between reality and a dream. They stood at the borderline of heaven and earth-immortal and yet vulnerable. Their ambivalence signifies a reversal of the Gilgamesh tragedy, for they are forever in the present but always in a state of uncertainty. Mazhar's recent work deals with subjects derived from Sufism-his Al-Hallaj series and Al-Niffari series. They show the ambiguous relationship linking Islamic mysticism with the artist›s inner vision.It is a theme that leads to a greater creative liberty by allowing him to search for his own truth in the realm of the imagination. The Al-Hallaj series radiates a light, sometimes bright and sometimes opaque, which interweaves fragments of calligraphic inscriptions and textures. Upon these subtle colour formations he throws talismanic signs such as open hands, magic boxes, reversed numbers, Egyptian eyes, and masks enclosed in triangles. This pictorial vocabulary facilitates the transition between tradition and modernity, and it bridges the spirit and the psyche. This is followed by the Al-Niffari series, where less hermetic images emerge and the shades brighten up. Changes noticeable in Mazhar's artistic choices are beginning to point toward a different sort of exhilaration. In 2002, Hani Mazhar visited Japan for the first time on the occasion of his East to East solo exhibition. His artistic sensibility was deeply impressed by the spirituality of Zen temples, and by the uncanny contemporary Japanese sense of design. More importantly, he discovered the importance of red and black, which he then incorporated into his palette. Speaking about his stay in Japan, the artist said, 'I felt like a stream returning to the spring of its origin.' From here on, he selected the path toward greater movement and growth, and expansion started to take place in every aspect of his life. The very recent Mogador cycle was born from his re-encounter with Latin American literature, a preferred subject of his youth when he read novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and other authors. This time his inspiration was provided by the novels of the Mexican writer Alberto Ruy Sanchez, especially The Secret Gardens of Mogador. Here, the body at the forefront of Mazhar's imagery becomes the instrument of the essential quest. The body is seen in ecstasy, elusive in its contortions. Male and female delight in their mutual intimacy by the fusing of their members, and are transfixed by the rhythm of life itself. These silhouettes, inhabited by the spirit of Eros, display an organic arousal poised between the abstraction of desire and the materiality of colour. This is carnal symbolism at its purest seeking to unveil the initial mystery as the soul moves upwards. The Mogador series is the product of a relationship fraught along the open borders of related ideas that at a special moment are bound to intersect and fructify. The rapport between the word-image of the writer and the image per se of the painter is multiplied, resulting in yet another level of significance. Mazhar's artistic survival has often depended on the double isolation he experienced, first in his own country, and then in his community of exile. To borrow a phrase from Homi Bhabha once again, Mazhar stands 'at the interstitial passage between fixed identifications of reality.' Born in Iraq, living in Britain, and looking toward inspirational sources coming from Japan and Mexico, Hani Mazhar is an artist working on the borderlines of many cultures and crossing through many ages. His works create a profound sense of newness through their insurgent acts of cultural translation. Astrid de los Rios |

|

|

|

E-mail: info@hayhillgallery.com |

Born

in 1955, Iraq. Samawah - British nationality.

Born

in 1955, Iraq. Samawah - British nationality.