home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase |

||||

AUGUSTE RODIN

COLLECTION OF AUGUSTE RODIN FOUNDRY PLASTERS This collection of foundry plasters has been assembled over several years with the intention of reproducing a limited edition of Rodin bronzes of the highest quality. In fact, using the finest craftsman and techniques developed by Rodin's fondeurs, bronze casts were created with the utmost attention to the details, size, and patinas which exist in casts supervised by the artist during his lifetime. With this purpose in mind, lifetime casts were examined, and the foundry plasters selected were those which maintained the details and quality of Rodin's best works. Plaster was the form in which Rodin recorded his genius. First modelling in clay, which disintegrates over time, Rodin recorded a composition's important stages and finished form by making a negative mold (un moule bon creu) from the clay. He then used this mold to cast a permanent form in plaster. A plaster was always the starting point for further innovations in the composition or replication in bronze or stone. The goal of this project has been to collect examples of Rodin's most significant works. These examples include, among others, such universally renowned figures as "The Age of Bronze", "Eve", "The Kiss", and "The Thinker". COLLECTION OF BRONZES FOR SALE The collection consists of a series of over 50 different Rodin sculptures, from which will be cast limited number of pieces each, with a certificate of authenticity. This document guarantees that the bronze was cast by the lost wax process from a foundry plaster. Each bronze is finished using the exact same patinas and techniques as used during the life of the artist. All dimensions and details are exact to life time casts. Each cast is numbered.

A book has been produced documenting the history of the foundry plasters, the high quality, validity, and importance of this collection, and the bronze casts derived from it. The book was printed by Arti Grafiche Amilcare Pizzi S.p.A., one of the premier art book printers, with contributions from notable people, and photographic work done by Mario Carrieri (considered the foremost photographer of sculpture). Legal rights with respect to recasts from foundry plasters of Auguste Rodin The Auguste Rodin bronze casts using the foundry plasters is authorized by the laws of the United States, countries of the European Union, countries of South America, and Asia. More specifically, this work is lawful under both the copyright, and moral rights statutes that have been enacted in these countries. With respect to copyright law, the United States, Europe, South America, and Asia provide that all copyright in a work expire seventy (70) years after the death of the author. Since, Rodin died in 1917, all copyright rights in his works, including these plasters and the works previously created with them, terminated in 1987 with exception of France, which terminated in 1989 for reasons particular to France's national history. Moreover, recasting of the Rodin sculptures is supported by the philosophy underlying the copyright laws. Copyright regimes enable an artist to control and profit from their work, thereby encouraging artistic endeavour for the benefit of the artist and the general public. However, copyright theory also posits that the public's interest eclipses that of the artist's heirs or assignees over time and that it is better served by termination of private control over copyrights after the passage of several generations. That time has expired for Rodin's works and, therefore, there is no longer any copyright bar against their re-casting. The few rights that remain to an artist's estate or assignees after transfer or termination of copyright rights are referred to as moral rights, or droit moral. These rights are strongest in France but they exist in varying forms in a number of other countries. They include:

These Rodin casts, however, do not implicate the droit moral for several reasons. First, they are not lifetime casts, but rather recasts from foundry plasters. Therefore, the moral rights related to physical control over the works, such as the rights of withdrawal, alteration and publication, do not extend to them. Moreover, the re-casts do not alter the plasters or the image embodied in the Rodin originals and, therefore, they do not involve the droit au respect de l'Oeuvre. Finally, all the bronze casts contain accurate attribution, thus respecting droit a la paternite and avoiding any confusion regarding the origins of each work. Most people do not realize that the vast majority of the bronzes that currently come to the market place today, whether in action or being sold in a gallery are posthumously cast. In fact many of the Rodin bronzes found in museums and public exhibitions have been cast after the life of the artist. Techniques used in the bronze casts The Rodin casts are cast using the lost wax process (the process preferred by Auguste Rodin). All casts are under the direction and supervision of experts and are done in one of the finest foundries in the world located in Italy. All processes and techniques replicate in exact details of those used by the artist during his lifetime. These casts are equal in all details to lifetime casts and are among the finest casts ever done from this remarkable artist. All patinas are done using the same chemicals and techniques of the lifetime works and are identical to lifetime casts.

Auguste Rodin is generally recognized as the most important sculptor of the nineteenth century. Born to a family of modest means in 1840 and slow to gain recognition, Rodin nonetheless won five of France’s largest commissions for monuments during the 1880s and 1890s. During these decades he produced grand public works and a vast oeuvre of drawings and small sculptures. By 1890 Rodin had become the most renowned sculptor in France; by 1900 he had achieved international recognition. His innovations in form and subject matter established his reputation as the first master of modern sculpture. Rodin’s fame and productivity have been matched by only one artist in the twentieth century, Pablo Picasso. Rejected by the state-sponsored art school, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Rodin was one of the few self-taught French sculptors of the nineteenth century. He moved from novice to sculptor’s assistant (praticien) without benefit of prolonged academic training. Rodin learned about techniques on the job and about style by studying in the galleries of the Louvre. Devoted to Greek and Roman art, he also studied the masters of the French Renaissance, Germain Pilon (1528-1590) and Pierre Puget (1620-1694). Not averse to learning from more contemporary masters, Rodin looked for guidance to François Rude (1769-1815), James Pradier (1792-1852), and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875). Rodin’s career can be divided into four phases: training and apprenticeship (1854-76), maturity (1877-89), zenith (1890-1901), and final years (1902-17). Each of these periods was characterized by a defining event. After a decade of living in poverty and working for other sculptors, in 1876 Rodin made a pilgrimage to Italy. His study of antique sculpture, Michelangelo, and other artists of the Italian Renaissance provided the necessary impetus for him to make the transition from Rodin the gifted artisan to Rodin the artist. In 1880, after his submissions to the Salon were accorded modest success, Rodin received the commission for the huge bronze doors for a proposed Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Work on the doors, now known as The Gates of Hell, coincided with Rodin’s reading of Baudelaire and Dante, kindred souls who inspired his art of the next decades. Two great exhibitions, both held in Paris, bracket the height of Rodin’s career: the 1889 exhibition at Galerie Georges Petit, which he shared with Claude Monet; and the grand retrospective that he installed in his own pavilion on the pont d’Alma for the Universal Exposition of 1900. The Georges Petit exhibition sealed Rodin’s position as France’s premier sculptor and opened doors to collections and museums around the world. After the close of the Universal Exposition in 1901, Rodin reerected his pavilion beside his villa-studio in Meudon. This first "Musée Rodin," the pavilion was the artist’s last completed public project; it became a perpetual monument and salesroom for him. He had become a living legend. Great commercial success and modest innovation marked Rodin’s final years, which he devoted largely to creating drawings, assemblages, and small-scale works, and looking after his collections of antique sculpture and contemporary paintings. The subject of numerous biographies, Rodin remains largely a riddle. Despite the fact that his life is accompanied by vast documentation, the motives of his personal life and career are often difficult to fathom. His personality encompassed the simultaneous expression of intensely private and grandly public personas. In her exhaustive and deeply probing biography of the artist, Ruth Butler summarized his personality as "lonely."1 Conventional in his tastes, he held to the opinions and prejudices of a lower-middle-class upbringing: until the last phase of his life, he preferred to live in humble circumstances without such modern improvements as heat and electric light. Despite modest accommodations and a mind-numbing work schedule, Rodin was never intellectually insular. He accrued a wide knowledge of art and literature and an extraordinary range of human contact. Yet he had few friends. Rather, he had colleagues and defenders-including some of the most powerful cultural personalities and politicians of his day-and enemies in abundance. Although generally awkward in public, Rodin could be courtly and effusive in audiences, elegant and open in his written correspondence and interviews. The key to Rodin’s life was his relationships with women: his strong ties to his sister, who died when he was twenty-two; a lifelong union with Rose Beuret, whom he married only at the very end of their lives; and a heartbreaking affair with Camille Claudel, from which neither participant ever fully recovered. These ties formed the tragic core of a personality that also sought out relationships on many levels with a host of female artists, models, dancers, fortune hunters, grandes dames, and aristocratic soul mates. Throughout his maturity, Rodin was deeply committed to these erotic and intellectual liaisons, attachments that were a primary source of his creativity. Convinced early on that he was a great artist, Rodin was as determined to establish his reputation as he was prolific and audacious in his production. From 1872 to 1885 Rodin worked incessantly until he gained the status and network necessary to produce major commissions. Especially in his later years, the role of Rodin the entrepreneur who managed several large ateliers and the simultaneous production of multiple commissions drove the Rodin the artist into ever more idiosyncratic refuges. Stays in various hideaways and increasingly emotional approaches to drawing and making small sculpture provided some relief from business and personal pressures. Despite conflicts, rejections, and his ineptitude as a public figure, Rodin managed the most complex career of his age with more skill and success than any other artist of his generation. Although Rodin’s materials and methods for making sculpture were not novel, even his earliest figures are original. To the academic practice of creating a balance between nature and an ideal, Rodin brought three innovations: an equal attention to every detail of the work; an insistence that the figure itself is the subject, not that the figure portrays a subject; and the dynamism supplied by complex asymmetrical axes. Such innovations would have remained intellectual and technical were it not for the genius of Rodin’s hands. He had a superb, unmatched gift for modelling clay and plaster. Rodin was able to translate his immense passion for work and his abiding love of the human form into thousands of small and many grand works, the animate patterns of solitary genius. "Nature" and "movement" were terms used by Rodin as touchstones for making sculpture. Following nature, which Rodin insisted was essential for a work of value, meant working from a model. The initial stages of creating a form involved drawings and clay sketches, which he manipulated until he had selected a pose and scale for a fully modelled work in clay. For both small and large figures, he worked from the live model to develop a series of profiles. Normally, Rodin employed professionals from Paris; however, for commissions with important historical themes, such as The Burghers of Calais, he sought out individuals with the same origins and from the same regions as the historic subjects. To imbue his figures with movement, or "life" (another of his terms), Rodin returned to his models in session after session, making additions, new profiles, and other changes. Only when the clay figure possessed the required movement-in terms of both implied motion and animate surface-did Rodin proceed to make an image in plaster or another medium. During his career, Rodin pulled hundreds of molds from his clay models. He then made plaster casts from these molds, casts that he would sometimes modify. The majority of Rodin’s innovations and refinements involved plaster, the medium he favoured not only for experiments and improvements of a work but for first exhibitions in the Paris Salons and gifts to friends and patrons. His involvement in casting his works in bronze was limited to his choice of mold makers, foundries, and patinators, whose work he supervised with exacting care. Perhaps because in his early years he had been required to carve stone for other artists, once successful, Rodin limited his work in marble to shaping key details and adjusting final finishes. In theory and practice Rodin emphasized a link, not merely between the physical and the spiritual, but also between the sensual and the spiritual. Such a dynamic had been developed by Renaissance and baroque masters, but Rodin’s work is unique in the intensity and omnipresence of sensual themes, in his monuments as well as in his smaller creations. Rodin never tired of female subjects. Their beauty, energy, and sexuality-expressed in figures dancing, falling, walking, and writhing-became the primary themes of the private work of his late years. These forms, sometimes abbreviated or reduced to a hand or a torso, often repeated with small variations and always animate and sensual, expressed the aesthetics of the fragment, of a work always in process. During the final stages of his career, Rodin learned to abandon, or to release, his forms from completion, rather than force them into a finished state. He also learned to create by assemblage and by subtraction and also that the process of making, rather than of developing explicit meaning, was the primary activity of his art. Rodin distilled this process into the phrase "to work well." The aesthetic of the fragment and the studio as the final shape of art constitute Rodin’s legacy for modern sculpture. Movement and sensuality were not, of course, Rodin’s only themes. His great individual figures and best monuments reveal a depth of feeling for humanity and a nobility of thought that place them among the finest works of European sculpture. The human and historic content of The Thinker and The Burghers of Calais transcends the circumstances of their making, establishing a rapport with past masterpieces by Donatello and Michelangelo as well as with works by twentieth-century masters. Rodin’s sculpture has an accessibility and breadth often lacking in works by even his most gifted contemporaries. This universality looks forward to the sculpture of Alberto Giacometti and Henry Moore. Rodin’s position is now assured, even though it was not so at the end of his life. The momentous changes in art of the first decades of the twentieth century made Rodin’s work and way of working seem anachronistic. After his death in 1917, curators at the Musée Rodin inventoried his collections and issued casts, principally through the Alexis Rudier foundry, but Rodin’s reputation went into eclipse between 1930 and 1960. His achievement was so great, however, that beginning in the 1960s a number of extraordinary scholars began to re-examine his life and work. This re-evaluation has led to a series of internationally significant exhibitions and publications and to the reestablishment of Rodin’s reputation as one of the great masters of European art. 1. Ruth Butler, Rodin: The Shape of Genius (New Haven and London, 1993), p. 514. 2. The disparity between the

content and techniques of Rodin’s personal works and these features in

his large commissions has been a major point of discussion in

scholarship over the last three decades. Modernist critics have

generally disparaged the bronzes and marbles because Rodin, in keeping

with nineteenth-century academic practice, delegated their execution to

his foundry men (fondeurs) and praticiens.

BRONZES LIST

|

|

1.

The Great Thinker - Height: cm.183 ( 72") |

30.

Dance Movement D - Height: cm.32 (12 5/8") |

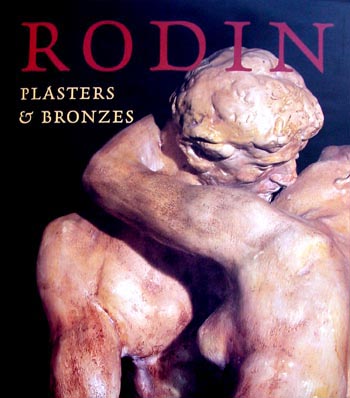

BOOK

BOOK