home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase

home

about

artists

exhibitions

press

contact

purchase |

||||

|

EXHIBITION OF OLEG PROKOFIEV |

||||

|

Rossica, Issue 9, Winter 2003,

Pages 44 - 49

Oleg Prokofiev (1928 - 1998) To coincide with the Prokofiev 2003 festival, Academia Rossica in collaboration with the Hay Hill Gallery has organised an exhibition of painting and sculpture by Oleg Prokofiev, the composer's son. 3 -29 March 2003, Mon - Sat, 11 - 6 pm, 11B Hay Hill, Mayfair, London W1 Some day Oleg Prokofiev must become the subject of a full-scale biography. Although in status he cannot be expected to match his father Sergei Prokofiev, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, nevertheless he is a significant and interesting cultural figure in his own right. Oleg Sergeevich was born in 1928, in Paris, where his father's family had emigrated. The Prokofievs decided to return to Moscow In 1936, where Oleg remained for the next 35 years. In 1948 his mother was sent to a prison camp, his father died on 5 March 1953, on the same day as Stalin, aged only 62. Oleg was brought up with a clear understanding of the historical fate of contemporary art. Family life was steeped not only in the music of his father and other composers but also in the plastic arts, and above all in painting. Many outstanding artists of the early 20th century regularly visited the Prokofievs' home and produced portraits of Oleg's father. The sheer variety of their creative styles evidently had an impact on Oleg's artistic awareness. Meanwhile he studied painting with Robert Falk and embarked on his own journey of artistic experimentation. Experiment was a keynote in all that he attempted. Despite Picasso's remark to the effect that he never searched for anything but only found things, the work of a true artist involves a continual search, continual doubt. In Moscow Oleg met a young English art historian, Camilla Gray, author of a ground breaking study of Russian avant-garde The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922. Clearly Camilla and Oleg discussed the subject from every angle, and the fact that this concept of 'experiment' became the leitmotif of the book surely reflects the understanding and perception of modern art not only of Camilla Gray but also of Oleg Prokofiev. The publication of the book infuriated Soviet officials, and Camilla and Oleg were not allowed to see each other for six years. In 1971, just, two years after they were eventually allowed to marry, Camilla died. Oleg took her body to England for burial, and decided not to return to Russia. He remained in England until his own death in 1998, by which time his works were at last exhibited in Moscow and even made their way into the collections of the Tretiakov Gallery. An early phase of Oleg Prokofiev's 'experiment' were his initial attempts to combine painting and the plastic arts, colour and the construction of space - in other words, to achieve a synthesis of those plastic elements which over the previous thousand years had become firmly detached from one another. In Russia, Malevich and Tatlin, Pougny and El Lissitzky, among many others, were setting themselves similar tasks. In the West, Hans Arp, Joan Miro, Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp were experimenting in the same area. The main characteristic of Oleg Prokofiev's colouristic plasticity is its linear nature. His constant theme is an endless meandering line, a certain plastic bulkiness and a strip of colour stretched and bent in space. In Russia in the 1950s Turetsky, Slepyan and Zlotnikov were also working on these problems but Prokofiev was the only one for whom the plastic motif of a line in three-dimensional space, as a sort of vestige of the development of this theme in time, was of fundamental significance. The others were looking at ways of articulating a blob, line or pencil-stroke not in relation to time, but to a plane. For these painters art was an experimental investigation akin - at times - to scientific research. The results had nothing in common with salon art or with the desire to create objects for relaxed contemplation. These were laboratory experiments, the latest of which was always a continuation of those that preceded it. Such visual experiments were, in a sense, comparable to what physicists were doing at the beginning of the last century - making innumerable photographs in a Wilson cloud chamber in order to observe the trajectories of scattering ionising elementary particles. Today one can see in this a certain naivety, but we should not forget that the motive force of these experiments (and here they were directly continuing the experiments of Kandinsky and Malevich) was the utopian hope of finding in art the key to a more sublime truth than art itself, to find the ontological foundations of being, in which falsehood, preening self-absorption and self-imitation could have no place. The pure ethical structure of the intentions of these young people in the 1950s was opposed to all non-independent art, whether subordinate to the Old Masters (whose discoveries seemed plainly anachronistic in the age of nuclear physics and space flights), or whether subordinate to the political authorities (who demanded that artists produce not truths but merely illustrations of the official ideology). Today such experiments have already become objects of historical connoisseurship and commercial exploitation, but we should not underestimate the risks that were involved at the time. In Russia of the 1950s this approach to art flatly contradicted the guidelines drawn up by official Soviet art, it was entirely selfless, an altruistic self-sacrifice, a ceaseless striving towards the ideal. By the end of Oleg Prokofiev's life the ascetic severity of his 'experiment' had little by little given way to freer and more lyrical forms of selfexpression. Even Malevich, we might recall, returned to figurative painting in the second half of the 1930s; and Picasso moved away from cubism and towards pseudo-classicism. The reasons for this apparent 'retreat' are not easy to understand. It was less to do with a re-evaluation of the utopian nature of the earlier project, and more to do with a change in the graphic material used in the experiments. At the same time one can see a very important thematic affinity between Oleg Prokofiev's abstract sculptures and his post-Impressionist paintings. The link lies in the attempt to embody both order and chaos, both the movement towards order and the destruction of order, the dialectics of creative consciousness between the poles of form and formlessness. This very formlessness, at times expressing itself in the infinity of plastic variations on the basic theme, was prompted by the desire to get away from the classicist self-sufficiency of form, from form as a changeless plastic figure that is there to be found and revealed. Instead Prokofiev introduces time into his work: time as an elemental force which destroys this plastic ideal. But alongside time that continually changes and transforms the fruits of human endeavour, we also have here time that consumes its own children, a nightmarish Chronos. In the figurative canvases of Oleg Prokofiev this theme is less pronounced than in his abstract works. It acquires the softer features of human oscillation between hope and feasibility. Here it is as if his draughtsmanship becomes somewhat infantile, almost like uncontrolled sketching; as if colour is added somewhat mechanisticatically in semipointillist daubs. Here Prokofiev is not so much continuing his earlier line of experiment, irrespective of the results already achieved by Matisse, Dufy, Soutine and Kokoschka; rather he is playing with variations of their creative achievements. Not that he is in any way sacrificing his own intuition or relapsing into imitation. Here order and chaos are no longer used as allegories of good and evil but instead they become another embodiment of time, which cannot permit that which has happened to obscure which is happening. In other words, here on the surface we have the same old dynamics of becoming and motion, that always engaged Prokofiev and gave him the strength to overcome life's adversities. Life, as it revealed itself to Oleg, was always full of chance happenings and tragic, irreparable losses. But in a sense this is not only life's natural disharmony, but also its harmoniousness, without which one could not possibly visualise either its freedom or its eternal movement. The artist ascends to justify not so much the evil of this life as its merciless blindness, which is merely the flip-side of vision. At any rate, for Oleg Prokofiev only this combination of chance and determinism, chaos and order, vision and blindness made it possible for him to create beauty which is commensurate with his time and with his age. In this sense his work continued the artistic quests and discoveries both of his father and some of the other great artists of our time. Alexander Rappaport is a Russian

art historian living in London. His article on

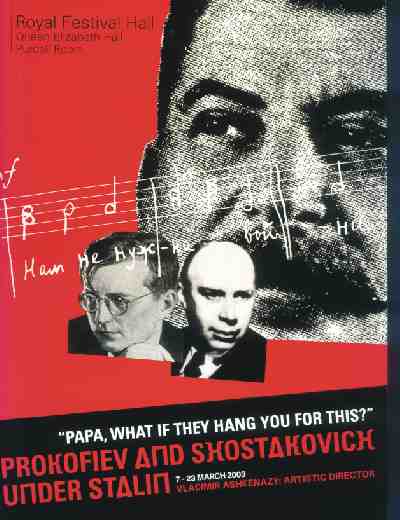

Programme of the concerts "Prokofiev and

Shostakovich Under Stalin" at the Royal Festival Hall

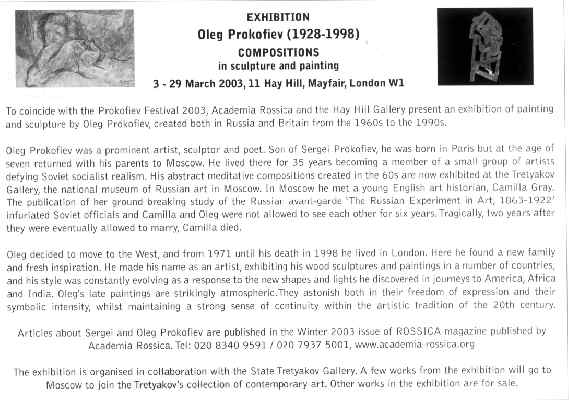

EXHIBITION To coincide with the Prokofiev Festival 2003, Academia Rossica and the Hay Hill Gallery present an exhibition of painting and sculpture by Oleg Prokofiev, created both in Russia and Britain from the 1960s to the 1990s. Oleg Prokofiev was a prominent artist, sculptor and poet. Son of Sergei Prokofiev, he was born in Paris but at the age of seven returned with his parents to Moscow. He lived there for 35 years becoming a member of a small group of artists defying Soviet socialist realism. His abstract meditative compositions created in the 60s are now exhibited at the Tretyakov Gallery, the national museum of Russian art in Moscow. In Moscow he met a young English art historian, Camilla Gray. The publication of her ground breaking study of the Russian avant-garde 'The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922' infuriated Soviet officials and Camilla and Oleg were not allowed to see each other for six years. Tragically, two years after they were eventually allowed to marry, Camilla died. Oleg decided to move to the West, and from 1971 until his death in 1998 he lived in London. Here he found a new family and fresh inspiration. He made his name as an artist, exhibiting his wood sculptures and paintings in a number of countries, and his style was constantly evolving as a response to the new shapes and lights he discovered in journeys to America, Africa and India. Oleg's late paintings are strikingly atmospheric. They astonish both in their freedom of expression and their symbolic intensity, whilst maintaining a strong sense of continuity within the artistic tradition of the 20th century. Articles about Sergei and Oleg Prokofiev are published in the Winter 2003 issue of ROSSICA magazine published by Academia Rossica. Tel: 020 8340 9591 / 020 7937 5001, www.academia-rossica.org The exhibition is organised in collaboration with the State Tretyakov Gallery. A few works from the exhibition will go to Moscow to join the Tretyakov's collection of contemporary art. Other works in the exhibition are for sale. Russian Mirror, No.33, March 13, 2003, Page 22; No.34, March 27, 2003, Page 22 Oleg Prokofiev (1928 -1998) Mayfair Times, March 2003, Page 6

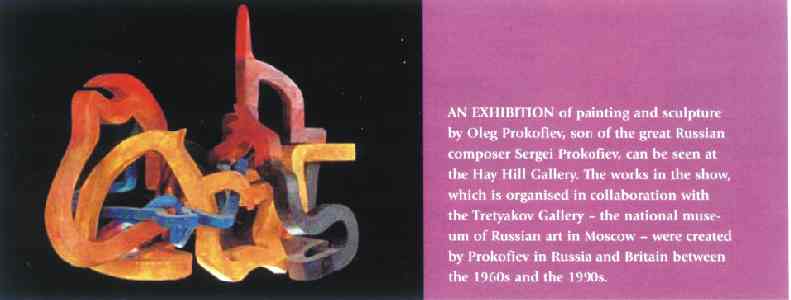

AN EXHIBITION of painting and sculpture by Oleg Prokofiev, son of the great Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev, can be seen at the Hay Hill Gallery. The works in the show, which is organised in collaboration with the Tretyakov Gallery - the national museum of Russian art in Moscow - were created by Prokofiev in Russia and Britain between the 1960s and the 1990s. |

||||

|

|

||||